Lost At Windy River By: Trina Rathgeber

My sister Trina, we were born and raised in Thompson, a small northern Manitoba community known as the hub of the North. We played hockey on our back yard rink and in the local arena together. We also played baseball on the expos coached by our dad and his fiend Marty.

Me and Trina ran through the forests with our life long friends. I was her pesky big brother who was always in trouble.

We used to love to go visit our grandma and young aunty Melissa I thought of it as a big adventure. Also going fishing and exploring at the lake with her was always exciting.

I am so proud of Trina she was at the time the youngest girl to try out for the Canadian woman's Olympic hockey team at age 17. She was so close to making it, but due to internal politics and a couple of mishaps she never made it to the Olympics. She played professional hockey in Europe and won a W.N.H.L. championship.

She is Married to an amazing husband Greg and a beautiful talented son named Owen.

I am so proud that my sister took the initiative were so many others in our family just talked about writing a book. Trina spent years tirelessly researching and sacrifice to her family to be sure to preserve the historical documentation of my grandma being lost in the barren lands. She wrote a novel which has not been published but the graphic novel has been.

We are very grateful that Trina was able to make sure that this historic chapter in our family history was preserved to honour my grandmother's legacy Lady Of The Thunderbird's for our family and future generations here on Turtle Island to learn from.

Grandma would be so proud of you Trina!!!

Lost At Windy River

Sometimes the most important stories are the ones that get taken from us, twisted, and told by voices that were never meant to carry them. Today, I want to share something deeply personal, a story about my sister Trina's powerful work to reclaim our grandmother's truth and set the record straight after decades of having our family's survival story stolen and distorted.

When Outsiders Take Our Stories

There was a story being told on a train by my great grandfather Fred Schweder travelling to Churchill Manitoba. Overhearing the story was Dr Francis Harper from the Smithsonian Institute from Washington DC and the 18 year old Farley Mowat. They were on an expedition looking for animals to take back as specimens to the museum. After finding out that our family was legendary trappers they knew they found who they were who they were looking for.

Farley Moore spent 12 days with our family taking notes the entire time And he's painted a picture for people around the world of what it's like in the northern regions of Turtle Island. In our territory he is know as "Hardly Knows It". He made up fantastical stories acting as if they were fact when they were truly fiction. Mowat has done irreversible damage to many people in the North with his stories

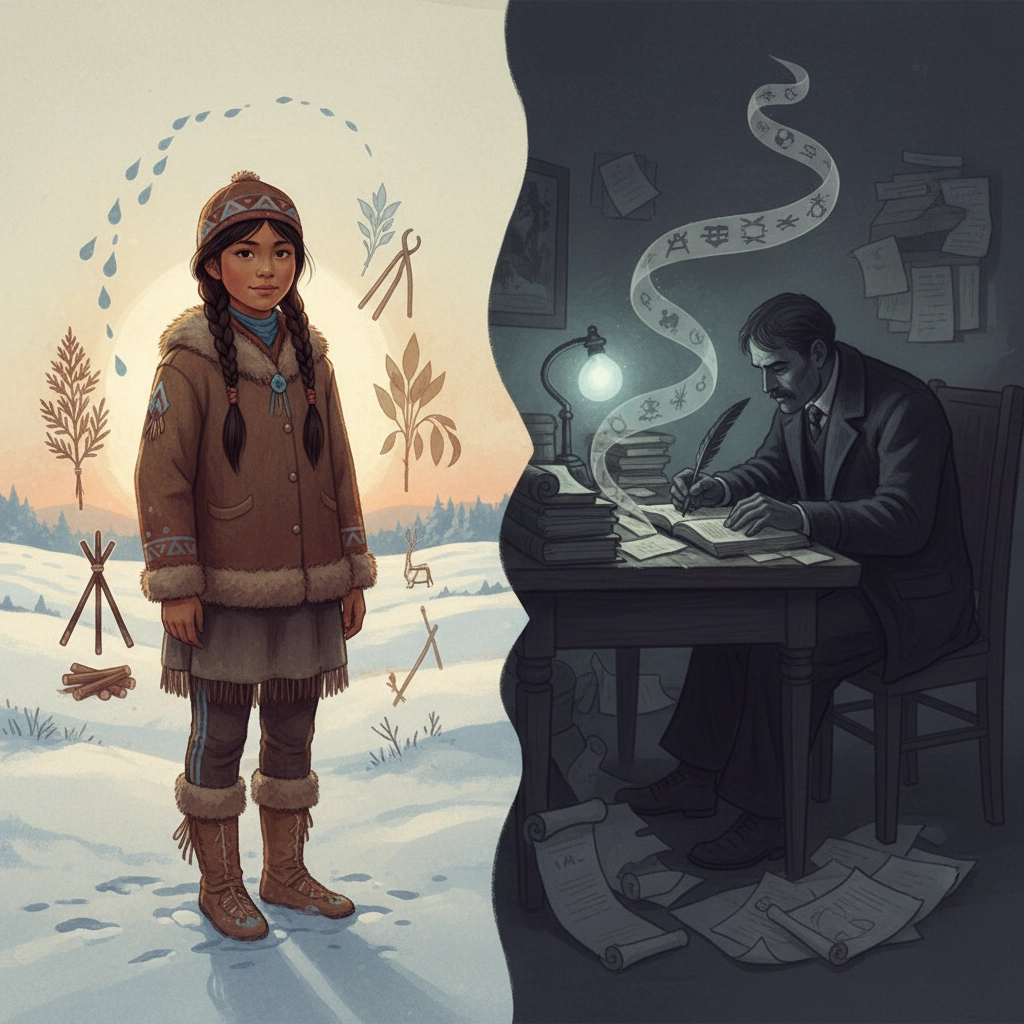

Back in 1952, Mowat published a book called "People of the Deer." Sounds innocent enough, right? Except buried in those pages was a chapter inspired by my grandmother Ilse Schweder's incredible survival story, a story he had no right to tell, especially not the way he told it. My grandmother, whose Cree name Iskwew Pithasew translates to "Lady of the Thunderbird," always felt strongly that it was her story to tell, not his. She carried that feeling with her until she passed, and now my sister Trina has stepped forward to honour that truth through her graphic novel "Lost at Windy River: A True Story of Survival."

This isn't just about one book or one family. This is about a pattern that's been happening to Indigenous peoples for centuries, outsiders swooping in, taking our stories, our experiences, our sacred knowledge, and packaging it up for their own benefit while we're left watching our truths get mangled beyond recognition.

The Real Story: Nine Days in the Barrens

Let me tell you what really happened to my grandmother. In 1944, thirteen-year-old Ilse was living with her family at the Windy River Trading Post in northern Canada. The Schweders were skilled fur traders who knew how to survive off the land, this was their life, their expertise, their home territory. What should have been a routine three-day trip to check the family's trap line turned into something that would test every piece of Traditional Knowledge she'd ever learned.

During a massive snowstorm, Ilsa became separated from her brothers. Suddenly, this young Cree girl found herself alone in the unforgiving barrens with no food, no supplies, and temperatures that could kill. For nine days, she faced down freezing cold, wild animals, snow blindness, and frostbite. She drew on everything her family had taught her about the land, about survival, about the connection between people and the animals and the earth itself.

When Swedish-born trapper Ragnar Jonsson finally found her, she was near death. He recognized the seriousness of her condition and helped reunite her with her family. But here's the thing, this wasn't some romantic adventure story like outsiders love to spin. This was a young Indigenous girl using centuries of accumulated wisdom to survive against impossible odds.

My Sister's Act of Reclamation

Trina didn't just wake up one day and decide to write this book. She spent years conducting extensive interviews with our grandmother before she passed, making sure every detail was right, every memory was honoured. She wasn't content to rely just on family oral history either, she dug through the Hudson Bay Archives, searched for any mention of the Schweder name, consulted with northern historian Les Oystryk who provided documents about our family and the Windy River Trading Post.

She interviewed our great-aunt Mary, who despite being in her late eighties, remembered vivid details about life at Windy River and the frantic search for Ilse. This is how you honour a story, with patience,and respect.

The graphic novel format itself is an act of reclamation. Illustrated by Alina Pete from Little Pine First Nation and colored by Jillian Dolan of Cree and Métis ancestry, this book is Indigenous-made from start to finish. Every visual element was crafted by people who understand the culture, the landscape, the significance of what happened. Alina worked from reference photos and historical images to make sure everything was accurate, the clothing, the environment, the time period.

This collaborative approach by Indigenous creators stands in stark contrast to some outsider writing about experiences that weren't his to tell, without proper context, or cultural understanding.

The Harm of Stolen Stories

I need to be real with you about what it feels like when someone takes your family's story and twists it for their own purposes. It's not just about copyright or intellectual property, it cuts deeper than that. When outsiders appropriate our stories, they're not just stealing words on a page. They're taking pieces of our identity, our survival, our sacred knowledge, and turning them into entertainment for people who will never understand what those stories really mean to us.

My grandmother lived with the knowledge that her survival story, one of the most defining experiences of her life, had been filtered through someone else's lens, stripped of its cultural context, and presented to the world as something other than what it was. That's a kind of theft that leaves wounds across generations.

This pattern is so common it's almost predictable. Non-Indigenous writers, researchers, anthropologists, and storytellers have been mining our communities for "material" for centuries, rarely giving back to the people whose lives they've turned into content. They get the book deals, the academic careers, the recognition, while we're left watching our truths get commodified and distorted. In Mowats case making millions of dollars

Setting the Record Straight

Trina's book opens by directly addressing Mowat's appropriation, no beating around the bush, no polite academic language. She makes it clear that this is an act of reclamation, to tell this story the way it was always meant to be told. That kind of directness is necessary. We can't keep tiptoeing around the fact that our stories have been stolen.

"Lost at Windy River" isn't just about what happened to our grandmother during those nine days. It's about resistance. It's about cultural survival. It's about saying "no" to erasure and "yes" to truth-telling, even when it's uncomfortable, even when it challenges popular narratives that people might prefer to believe.

Every time an Indigenous person reclaims their family's story, they're pushing back against centuries of colonial violence that tried to silence our voices. They're saying our experiences matter, our knowledge matters, our way of seeing the world matters: and we don't need anyone else's permission to share what belongs to us.

Why This Matters Beyond Our Family

The work Trina has done with "Lost at Windy River" connects to something much larger than one survival story. It's part of a movement of Indigenous writers, artists, and knowledge keepers who are taking back control of our narratives. We're done letting other people speak for us, interpret our experiences for mainstream consumption, or turn our sacred knowledge into academic theories.

When you support books like Trina's, you're not just buying a graphic novel. You're participating in an act of justice. You're saying Indigenous voices matter, Indigenous stories deserve to be told by Indigenous people, and the truth is worth more than comfortable lies.

This is about future generations too. My grandmother's great-grandchildren will grow up knowing the real story of what happened at Windy River, not some sanitized or romanticized version filtered through a colonial lens. They'll understand that their ancestor was a powerful, knowledgeable woman who survived through skill, determination, and deep connection to the land: not some helpless victim waiting to be rescued.

The Unpublished Novel and Ongoing Work

Trina hasn't stopped with the graphic novel. She's also completed a full novel expanding on our grandmother's story: more details, more context, more of the truth that deserves to be shared. That book hasn't found a publisher yet, but I believe it will. The world is slowly waking up to the fact that Indigenous stories told by Indigenous voices aren't just "niche" markets: they're essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the real history of this continent.

Every time publishers or readers dismiss Indigenous-authored work as too specific, too challenging, or "not universal enough," they're perpetuating the same systems that allowed people like Mowat to profit from our stories in the first place.

A Call to Truth-Telling

I want to challenge everyone reading this to think about the stories in your own family, your own community. Who gets to tell them? Whose voices are being centered? Whose are being erased or distorted?

If you're not Indigenous, I encourage you to seek out books, art, and stories created by Indigenous people ourselves. Support living Indigenous authors. Question the sources of what you think you know about our cultures and histories.

If you are Indigenous, I encourage you to dig into your own family stories. Talk to your elders while they're still with us. Ask the hard questions. Don't let anyone else be the authority on your own family's truth.

The path Trina has walked with "Lost at Windy River" shows us what reclamation looks like in practice. It takes patience, research, respect for our elders, collaboration with other Indigenous creators, and the courage to directly confront the lies that have been told about us.

Our grandmother's survival in those barrens all those years ago wasn't just about staying alive for nine days. It was about carrying forward the knowledge, strength, and spirit of our people. Now, through Trina's work, that survival continues in a different form: the survival of our stories, our truth, our right to speak for ourselves.

That's the real power in reclaiming what was stolen from us. We don't just get our stories back: we get our voices back, our dignity back, our place as the authorities on our own experiences back.

And that, relatives, is how we keep walking forward, no matter what storms try to silence us.

All My Relations

Maskihkîy Muskwa

https://www.orcabook.com/Lost-at-Windy-River?srsltid=AfmBOoqGxGnjO5qMb9J0SOeK2vUlfSPX9GbX6ehI71G0JUcxyx91GTbq

https://www.amazon.ca/Lost-Windy-River-Story-Survival/dp/1459832264